Let us agree that the term “Counting Time” used in music means to locate the beats, and measure, and determine the value of notes and rests in the measures. This implies an actual measurement of time duration. When a metronome is set at 60, each beat is one second long, and a quarter note held for one beat has a duration of one second. A half note would have a duration of two seconds, an eighth, 1/2 second, and so on.

There is a sense of rhythm within our bodies which acts as a natural metronome to measure the beats in music. If music were written with notes only a beat long or multiples of that beat, no problem would be involved. What causes trouble is subdividing the beat accurately on all notes shorter than one beat.

An analysis of this problem reveals that, in large part, band music is written to use either eighth or quarter notes as units of measurement. In band music, these meter signatures appear often: 3/8-4/8-6/8; or 2/4-3/4-4/4. The half or sixteenth note, i.e. 2/2-3/2-4/2, or 4/16-8/16-, is used less often as a unit of measurement. In baroque and early classical literature, 2/4—3/4— 4/4 or meter signatures are often used to denote 4/8—6/8—8/8 or 4/4 respectively. This is especially true in slower movements which bear the tempo indication Lento, Adagio, or Andante. It is best to investigate this aspect of the meter signature before performing music of the baroque and early classical period. I have seen fairly fast rondos marked 2/4, which all authorities agree should be performed with 4/8 feeling. When the speed of the individual unit becomes slower than M.M. 60, it may be difficult to feel the rhythm. Thus, a speed marked M.M. 50 is easily comprehended when its unit is divided in half and played at M.M. 100; i.e. 4/4 M.M. 50 equals 8/8 M.M. 100. Conversely, 4/4 M.M. 200 is more easily comprehended at 2/2 M.M. 100. During rehearsals difficult passages may be broken down into different times. A simple illustration is found in Molique’s “Andante in F” for flute. This selection, in 3/8 time, is played three beats to the measure. One section goes into sixty-fourth notes, however. To learn this quickly and easily it must be counted and played in 6 16 time, six beats to the measure. After the technical difficulties are mastered, it becomes a simple matter to play the passage up to tempo, beating the measure in three, but counting it in six.

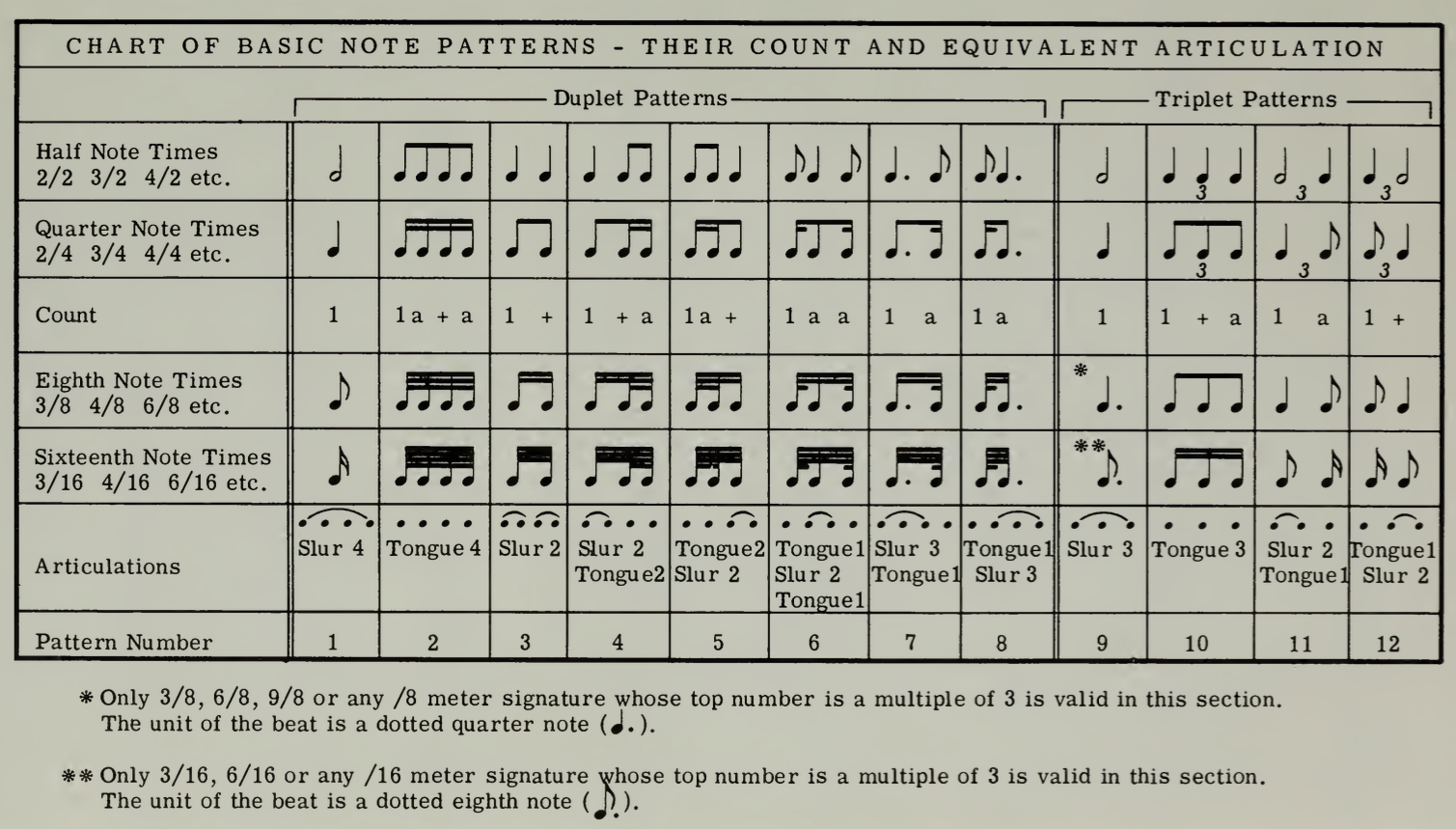

Going a bit further, we find that composers tend to make persistent use of basic groupings of notes, or, shall we say, time patterns. Twelve basic patterns are used continually. These can be compared to, in fact, even match the twelve basic articulations. Methods for counting, or measuring the patterns vary greatly. Perhaps a standard routine for doing this should be adopted and used by everyone. What a boon this would be to student and teacher; the student who, when he changes schools, may have to learn an entirely new method of counting time: and the teacher, who must make sure that every student understands the system of counting time used in his school.

Several systems for counting time are in use. For example, the band student, who through playing in the band learns that he must count time accurately, studies with a piano teacher who teaches a less accurate method for counting time used in older conservatories. Or perhaps this same student may join the school chorus whose conductor does not believe in counting time. This leads to confusion and an unnecessary loss of time. It would certainly simplify the work of the conductor in preparing a large massed group for performance, if performers and sectional coaches were well-versed in a uniform system of counting time. I feel confident that this idea will be adopted in the near future. I do not understand why persons who use a dictionary as a standard for spelling, who count pennies uniformly, and who have adopted a standard system for naming notes, cannot agree on a standard system for counting time.

For several years I taught without using a definite, accurate system for counting time. Finally I realized I was being unfair to my students, for I placed serious limitations upon their reading ability. I had failed to give them an accurate measuring device they could use without help from me. If students are never expected to play amthing but simple music, a hit or miss style of counting time is workable; however, when difficult music is

attempted, the picture changes at once. Careful teaching and use of die system soon to be presented makes it easy to break down difficult music into small segments, analyze it, learn it correctly, and then restore it to integrity. Those who comprehend this method have the tremendous advantage of knowing how to count time correctly.

Early in my career. I conducted a school band in which the best readers were students of a European-trained teacher who taught a definite system of time counting. Then I moved to a position in another city, and had an excellent opportunityto make an honest trial of his method in my own teaching. The system for counting time which is diagrammed is an adaptation of this method. It produced amazing and gratifying results. For instance. I discovered that the ability to teach fingerings and tone production, coupled with training in a definite system of counting time, produced young performers who could read and play “at sight”, With this method of teaching, given a minimum of guidance, I found that students were soon able to play music of advanced difficulty, music that often times I could not play on their instruments. Another amazing thing happened. My efforts in counting time for them were of great benefit to my own performance and conducting, and opened the door to music I had avoided because I was not confident of my ability to read, play, or conduct it.

Does this method have educational value, and is it scientifically sound? I think so—for these reasons:

a. It is a simple, easy, numerical system which locates the player in a measure exactly, and uses language learned in early childhood. It enables the player to know precisely where he is on the printed page. When I stand before a band in rehearsal, I want to be able to say to a section, “Folks, the last sixteenth note of the fourth beat in measure number sixty is F sharp.” In order to be really efficient, the time counting system must locate the performer and director in “numbered” measures, at precise fractions of the beat.

b. Subdivisions are counted by using syllables “ah”—”an”

Two notes to the beat, as in 2/4

Three notes to the beat, as in a triplet

Four notes to the beat, as in a group of four sixteenths

Since the “a” vowel is easy to enunciate, this system does not distort the sound of note groupings. The actual sound of a note group is conveyed to the performer’s mind instantly, surely, and precisely.

c. The syllables roll off the tongue rapidly and evenly. Say “one ah an ah two ah an ah” over and over again, rapidly. How much easier it is to say this than any other possible combination of syllables.

d. This system is easy to mark on the printed page.

1 an = 1 +; 1 an ah = 1 + a; 1 ah an ah = 1 a + a

and in fast 3/8, 6/8, 9/8 and 12/8 where the dotted half note is the unit measurement of the beat:

e. This system has been used successfully for years. I used it for twenty-five years, during which time I tried out every other method for counting time brought to my attention. I found no other system that offered the advantages of this simple method.

f. This system is logical because it is easy to learn and teach, especially when started at the very beginning of the student’s experience.

Before continuing, I offer these personal observations. Many school band conductors constantly plagued by a “lack of time,” make no attempt to be thorough in their teaching. Yet it stands to reason that when one is pressed for time, he should seek far more efficient and thorough methods of teaching. When students cannot count time, precious rehearsal time is wasted, lost forever.

A standard system for counting time has not been adopted because so little effort has been put forth in that direction by music educators.

Many instruction books contain exceptional material for self training, provided a good counting system is taught, and the count marked under the exercises being used.

Time counting is an accumulative experience which, when taught correctly from the very beginning, may be learned painlessly and thoroughly. It is almost impossible to teach a student to count accurately after he has played carelessly and recklessly. Moreover, most people offer an incredible amount of resistance to the acquisition of knowledge. Congenital laziness is not a popular subject to discuss, but persons afflicted with intellectual inertia may have this disease. An unwillingness to try out new methods, new ideas, embrace new concepts, seems to be an inherited trait among music educators. A little reflection reveals that unless we think about and try new things occasionally, we might as well be running a machine, doing the same thing over and over again, our days filled with monotony. How can we possibly be fair to our students unless we continually try to improve our teaching techniques?

There is no other way to grow and be happy and proud in one’s work.

Time counting must be done aloud, in a clean, snappy manner. Rhythmic patterns and note groupings can be memorized quickly if students count them aloud while fingering them on the instrument. This procedure enables the student to hear the count when playing. A little “gremlin” sits in his ear and counts for him, a most valuable asset when rests occur in music. This phenomena can be demonstrated easily and quickly. Count a few measures aloud, then continue the count, but silently. Note that the count will still be heard distinctly in the mind’s ear.

Counting should be done rhythmically. Our larger muscles constitute a metronome within the body. It will do much to clear up the confusion inherent to “time counting” if a distinct cleavage is made between the “count” and the “beat”. The “count” (or meter) is what we say; the “beat” (or rhythm) is what we do, or feel. Waltz time has one “beat” in a measure of three “counts’\ Six-eighth marches have two “beats” in a measure of six “counts”. (Interesting, though unrelated in terminology is our use of the words “note” and “tone”. A “note” is seen, a “tone” heard. No one ever heard a “note” or saw a “tone”.) Pianists, drummers, and string instrument players use large muscles when playing. Obviously, wind instrument players cannot, or at least, should not beat time with their bodies, if they are to feel rhythm, they must beat time with the foot. The only reason for doing this is to induce a strong, rhythmical pulsation in the large muscles. (One reason for not beating time with the big toe is that large muscles are not used, and no strong rhythmic sensation is felt.) Memory is at work when muscles develop a strong sense of rhythmical feeling. Try this demonstration: count the time for a simple tune like “America,” beating the foot vigorously and evenly, down and up. (No “sissy” little tap of the toes.) After going through the tune a couple of times, count time again, but keep the foot still. The rhythm will still be felt in the muscles. Now hum the song softly. Note that the “gremlin” will be heard counting in the mind’s ear, and the rhythmic impulse felt in the muscles. If anyone can dream up a sounder, more sensible, logical, expeditious, or easier method to teach counting, I would like to hear about it, a statement I make sincerely. I am the first to admit that it is a “pesky” job to teach time counting. The only method I have found to be psychologically and physiologically sound is the method outlined herein; however, I am still seeking a method which will permit me to say “presto-chango,” whereupon everyone will be able to read and play music perfectly.

When you try this method, really count aloud, and beat the foot, evenly and strongly. I ask students to beat with the left foot since this seems to jar the body less. Please do not be afraid to try this for fear that your students will tramp their way audibly through a concert. “Foot beating” at concerts is done by students who are not aware of it. When students are asked to beat with the left foot while counting time out loud, they are made aware of the muscular response involved. They will refrain from beating the foot at your request. Try this: rehearse a number and have students “beat” time with the left foot. Repeat the number and, at command, have the students cease “beating time.” (Observe that you can see the response of each individual to rhythm when he beats time with the left foot.)

An accurate method of counting time is absolutely essential to efficient sight playing. Concomitant with the ability to play at sight is the ability to analyze the printed page rapidly. Actually, this analysis precedes the muscular activity involved in playing. When learning to read ahead, at first the eye should be trained to encompass groups of notes, and the mind to hear the patterns of sound involved. Then both eyes and mind should be trained to read and comprehend entire phrases. This sort of “sight reading” and quick analysis demands a definite system of counting time.

Time counting requires daily drill and practice, and is a skill to be compared with that through which a fluent technique is attained. Everyone knows how quickly the fingers become “rusty” without daily practice.

Incorrect time counting may cause dissonances to sound which are not written into the score. For example, a clarinet section may be required to play a unison chromatic scale in a dotted eighth-sixteenth pattern. If only one player in the section plays it in equal eighth notes, a small fraction of each beat will be dissonant as tones a semitone apart sound simultaneously. Nor can it be argued that the tone produced by only one player is covered by the ensemble evenly. Incorrect time counting is a big reason for lack of clarity in performance.

When a student counts and beats time in supervised rehearsals and private lessons, he absorbs the system quickly, and it becomes a part of his subconscious reaction to performance. When the instructor counts time aloud and vigorously, he assists in creating a lasting mental impression in the mind of the student.

Parenthetically, it remains my firm conviction that a band conductor should continue to play on his major instrument, and reserve time each day for serious practice. When a director practices seriously, with definite objectives in mind, he will be on “his toes” and alert to problems involved in performance. Moreover, a conductor who plays one instrument well is encompassed by an aura of authority that enables him to teach more effectively. Being “creatures of action”, young people respect the teacher who “does” as well as “says”.

The chart below sets forth graphically the twelve basic rhythmic patterns, and the relationship of basic articulations. When using the chart, beat time evenly with the left foot, “down-up” for the first eight patterns. The foot starts up when the “an” is said.

The upbeat is as important as the down, and its foot action should be stressed. Pronounce the syllables for each pattern exactly where they come on the “down” or “up” beats. On triplet patterns the foot beats an even three, “down-stop-up,” and the syllables are pronounced in relation to this. Do not fret because pattern 10 uses the same syllables, “one an ah” as number 4. When pronounced as indicated, these will sound different. When this method is followed, the student is located exactly in each measure through a numerical count and the easily pronounced syllables that follow.

To learn this system in ten minutes, take a song book and mark the counts under the notes of a familiar song. Then count it aloud —and I mean “aloud”—while beating time with the left foot. Go through the song this way a few times. Xow hold the foot still, and hum or whistle the song. The “gremlin” will be heard counting in the minds ear. and strong, rhythmical pulsations will be felt in the muscles.

This to my mind is not as desirable as the first method, however, the introduction to Beethoven’s Egmont Overture while in 3/2 time is usually directed as though it were 6/4 time.

Here are a few tricky patterns which illustrate how this system may be adapted to unusual rhythmical patterns.

When rests occur, use the word “rest” in place of the syllable. When counting out a number of measures rest, like four measures of 3/4 time, say “ONE, two three, TWO two three, THREE two three, FOUR two Play. (In this day of globe-circling satellites, and the “Countdown”, many teachers advocate the following method for counting measure rests, “FOUR two three, THREE two three, TWO two three, ONE two Play.” Modern day students have little trouble in counting backwards.)

Previous Section: Rehearsing for Sight Playing — Next Section: Fundamental Music Theory